It occurred to me that to make a piece of music exactly 1000 years long not only solved the problem of how to “make” time, but added another dimension to the idea by opening up questions about music and sound, composition and duration. The simple idea that popped into my mind, “write a 1000 year long piece of music,” demanded solutions to an ever expanding range of questions; how to deal with changing cultural perceptions of music, how to listen to music too long to hear completely, where to place it, what technology to base it on, how to make it available to the public… and perhaps most importantly, how to plan for its survival. - Jem Finer

Listen now

Longplayer is a concept, the way it can be experienced by contemporary audiences must perpeually shift with the times. Its original form was a computer programme, generating the piece in real time; at the moment, you can also listen via an app, but future speculative formats include mechanical machines designed to play the work if the computers that play it at current ever become obsolete.

iPhone/iPad

This app requires no data connection and automatically synchronises itself with every other copy of the app across the globe. With this app you become part of a community of listeners distributed through space and time, across many lifetimes.

Desktop computer

To listen to Longplayer, live-streamed from Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse, London E14, download the m3u file above and then open in your media player (for example iTunes). Note: If your browser is Safari, this download may open a new page in your browser and play in the background.

2. If your media player enables open streams, copy and paste this link – http://stream.spc.org:8008/longplayer – to play the stream. Open Stream is under the File menu in iTunes.

How Longplayer Works

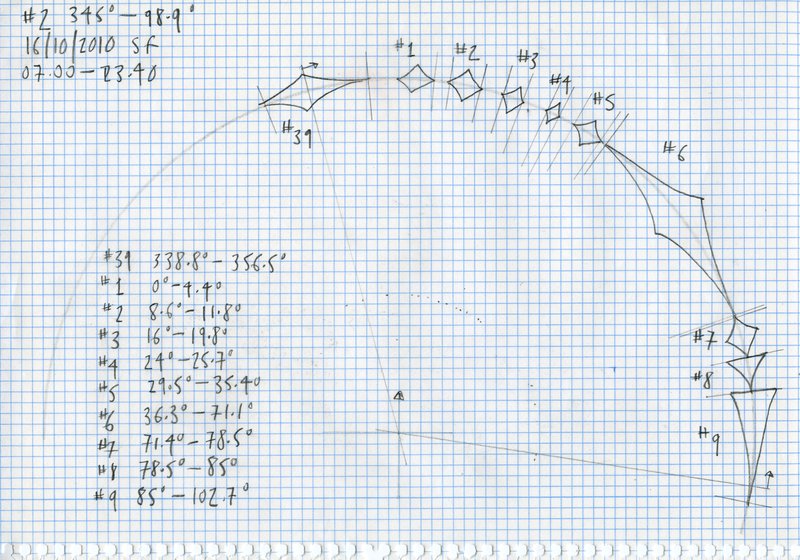

The composition of Longplayer results from the application of simple and precise rules to six short pieces of music. Six sections from these pieces – one from each – are playing simultaneously at all times. Longplayer chooses and combines these sections in such a way that no combination is repeated until exactly one thousand years has passed. At this point the composition arrives back at the point at which it first started. In effect Longplayer is an infinite piece of music repeating every thousand years – a millennial loop.

Audio: Longplayer Conversations

The Longplayer Conversations

Each year, as a way of celebrating the vision behind Longplayer’s long term aspirations, Artangel and The Longplayer Trust invite a leading cultural thinker to conduct a public conversation with someone they have never met, and to engage in a discussion inspired by the philosophical premise of a project which unfolds, in real time, over the course of a millennium.

The inaugural conversation took place in 2005 between New York artist and musician Laurie Anderson and Nobel prize-winning author Doris Lessing. Since then, meetings between thinkers have continued to take place as follows:

- 2005: Laurie Anderson and Doris Lessing. An excerpt is available on Longplayer.org

- 2007: Bruce Mau and David Adjaye. An excerpt is available on Longplayer.org

- 2008: Alain De Botton and George Soros. An excerpt is available on Longplayer.org

- 2009: The Long Conversation, a 12-hour talking marathon of 24 cultural figures. Available in full on Soundcloud

- 2011: John Gray and James Lovelock. Available on Vimeo and YouTube

- 2012: John Lanchester and Caitlin Moran. Available on YouTube

- 2013: Richard Mabey and Richard Holloway. Available on Vimeo and YouTube

- 2014: Brian Eno and David Graeber. Available on Vimeo on YouTube

- 2016: Marina Warner and Ali Smith. Available on Soundcloud

- 2020: The Longplayer Assembly, a 12-hour conversation relay live online. Available on YouTube.

As of 2016 all conversations except the 2020 Assembly are produced by The Longplayer Trust, and available to listen to on Longplayer.org.

Image: (left) Ali Smith and (right) Marina Warner in conversation at The Anatomy Lecture Theatre, King's College, London (2016). Photograph: Christian Payne

Writing

Longplayer Letters: Volume I

By a statistical argument, had nature not produced thin-tailed variations, we would not be here today. One in the trillions, perhaps the trillions of trillions, of variations would have terminated life on the planet. – Nassim Nicholas Taleb to Stewart Brand

Ideology and ghost stories are timeless. What I'm proposing is the difference between fiction and nonfiction, between imagination and reporting. — Stewart Brand to Esther Dyson

Read a chain of written correspondence on the subject of long-term thinking. Unfolding slowly over time, the Artangel Longplayer Letters are forming a written conversation in which each conversant is both answering his or her predecessor and thinking toward his or her successor.

The correspondences

Brian Eno → Nassim Nicholas Taleb → Stewart Brand → Esther Dyson → Carne Ross → John Burnside → Manuel Arriaga → Giles Fraser

The Longplayer Assembly

In 2020, the Longplayer Assembly marked the twentieth anniversary of Jem Finer’s Longplayer – a continuous piece of music commissioned by Artangel that began playing at the turn of the millennium, with a duration of 1000 years. Embracing the essence of Longplayer as a contemplation of time, the Longplayer Assembly echoes this continuity through its convergence of 24 participants, from around the world, whose individual specialist work embodies long term thought. Each speaker will converse in turn, passing the virtual baton every 30 minutes in a non-stop 12-hour live relay.

Audio: Artangel Podcast 1

Artangel Podcast 1: A decade, a lighthouse, a protest, a barber's

Part one of the first ever Artangel Podcast recorded on the 10 year mark of the projects duration on December 31st 2009 when the 1000-year long piece of music reached the 1% mark.

Speaking from the Longplayers original listening post at Trinity Buoy Wharf lighthouse, Jem Finer reflects on the origins, meaning and future of the composition. In September of that year he oversaw its transformation from an automated algorithm to a 1000-minute live performance: this feature includes excerpts from The Long Conversation, the epic 12-hour relay debate that accompanied this event. The excerpted speakers are Jeanette Winterson, Mark Miodownik, Sophie Fiennes, Daniel Glaser, Susie Orbach and Andrew Kotting.

Part two focuses on The Museum of Non Participation, an Artangel project conceived by Karen Mirza and Brad Buter in 2007.

Producer: Iain Chambers

You can listen to all Artangel Podcasts on Soundcloud.

Image: Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse (2000). Photograph: Stephen White

Longplayer has always served to remind us of times we cannot imagine. In this moment, the Longplayer app also makes us question our relationship to the gadgets we carry around with us. While most of us delete and download new tools as we upgrade, an app for a thousand years provides a still point at the centre of the digital universe. – James Bridle, The Guardian

Writing

Longplay Letters: Volume II

My hunch is this: that Eternalism, the long-player’s ultimate longplay, is located in residues of sleep, in the community of sleepers, between worlds, beyond mortality. I dreamed my genesis in sweat of sleep. — Iain Sinclair to Alan Moore

I’ve been thinking lately about the relationship between art and the artist, and I keep coming back to that Escher image of two hands, each holding a pencil, each sketching and creating the other (EscherSketch?). Yes, on a straightforward material level we are creating our art – our writing, our music, our comedy – but at the same time, in that a creator is modified by any significant work that they bring into being, the art is also altering and creating us. — Alan Moore to Stewart Lee

Read a chain of written correspondence on the subject of long-term thinking, from Iain Sinclaire to Alan Moore and from Alan Moore to Stewart Lee. Unfolding slowly over time, the Artangel Longplayer Letters are forming a written conversation in which each conversant is both answering his or her predecessor and thinking toward his or her successor.

Jem Finer

Jem Finer first collaborated with Artangel on Longplayer, a one-thousand-year-long musical composition that began playing at midnight on 31 December 1999. This collaboration has continued throughout the years marked by events including Longplayer Live 2009, the ongoing Longplayer Conversations series, and, most recently, with the Longplayer Assembly.

Known as an artist and musician, Finer is also an award-winning composer. His works include 'Score for Hole in the Ground' in which underground falling water plays on hidden percussive instruments. Meanwhile 'The Centre of the Universe' is a radio observatory of sorts, reimagined as a drawing machine and supercomputer, likened to a composing machine where the flow of ball bearings, carrying information through labyrinthine circuits of mechanical computational units, were used to calculate minimal melodic phrases.

Images: (left) Jem Finer during the performance Longplayer Live, September 2009 at The Roundhouse. Photograph: Bruce Atherton and Jana Chiellino; (above) Jem Finer, 2020.

It marks time like a sonic Stonehenge. — Mark Espiner, The Guardian

Beneath Longplayer’s simplicity lies something more complex. […] It also raises questions. For instance – why have we been duped into thinking that the new millennium’s all about one wild night? But Finer’s Longplayer is no protest against short-termism. — The Herald, 2 December 1999

The intention [of Longplayer] is that its droning and parping will, like this year’s eclipse, make the hearers ponder the passing of time in a way that makes you feel both mortal and insignificant. — The Evening Standard, Going Out, 30 December 1999

If infinity anxiety spawned the piece, it is performative anxiety that is now driving Finer. What if there were a power cut? What if there were a war or a natural disaster? What if the computer crashes? […] Longplayer mocks the temporary and limited zones of the Millennium Experience. It marks time like a sonic Stonehenge. There’s no real rush to catch it, it will outlive you, but listening to it in that lighthouse somehow makes you a part of its determined beam of sound. ‘The air is full of sound information,’ says Finer, ‘from the radio waves of mobile phones to an exploding star. I like the fact that its all going on around us. The fact that this piece just exists is reassuring.’ — Mark Espiner, The Guardian, 24 May 2000

Longplayer is […] more like a soundscape, or a piece of installation art, than a conventional piece of music. You can never experience it all. It will outlive you. If you listen to a fragment of it, you can but imagine the rest: the unknowable, ineluctable expanse of time stretching before you. — Charlotte Higgins, The Guardian Weekend, 9 September 2000

Longplayer was produced by Artangel with the support of the Millennium Commission and is now in the care of the Longplayer Trust. Artangel is generously supported by the private patronage of The Artangel International Circle, Special Angels and The Company of Angels.